–

A critical look at the current system and proposals for a more balanced approach

–

Tax credits offered on pension contributions are a cornerstone of retirement planning in the UK. The system is designed to incentivise individuals to set aside funds for their later years, with the added benefit of growing these savings in a tax-advantaged environment. While the principle is broadly applauded, the reality of how tax relief is distributed raises important questions of fairness, effectiveness, and sustainability. In this article, I explore the current structure, highlight what I see as its imbalances, and propose a series of reforms aimed at fostering a pension system that is fairer, simpler, and fit for purpose in the 21st century.

–

The Current System: How Tax Credits for Pensions Work

–

For the majority of savers, pension tax relief is granted ‘at source’—meaning that for every £80 a basic rate taxpayer contributes, the government adds £20 to make a total pension contribution of £100. Higher and additional rate taxpayers are entitled to claim back additional relief through their tax return: for a higher rate (40%) taxpayer, the total tax relief climbs to £40 per £100 contributed, and for additional rate payers, even higher.

–

This means that for someone who contributes £600 to their pension fund, and who pays tax at the basic rate (20%), the government tops up their pension by £150, resulting in a total contribution of £750. By contrast, a higher earner can claim a refund that takes their £600 contribution up to £1,000—a £400 uplift, representing 66.6% of their own money, compared to 25% for the basic-rate taxpayer. This reflects the fact that higher earners pay more tax, but also creates a significant disparity in the value of the government’s support.

–

A Question of Fairness

–

This disparity has long been a subject of debate. The current structure means that those who are already well-off receive the largest tax subsidies for saving—an outcome that may seem at odds with the goals of a progressive tax system. While it is true that higher earners contribute more in tax overall, the pension system arguably magnifies their advantage.

–

Consider that a higher-rate taxpayer could receive £400 in tax relief for every £600 they contribute, while a basic-rate taxpayer receives just £150 for the same contribution. Over a working lifetime, this difference is compounded, especially when combined with the power of investment growth and the ability of higher earners to contribute larger sums to their pensions.

–

The Annual Allowance and High Earners

–

Currently, there is a cap—known as the ‘annual allowance’—on the amount that can receive tax relief each year, set at £40,000. If someone were able to contribute the full £40,000, the basic rate tax relief would amount to £8,000, while a higher-rate taxpayer could claim up to £16,000 in relief.

–

Salary sacrifice schemes add further complexity. These arrangements allow both employer and employee to make pension contributions before tax and National Insurance is deducted, resulting in both parties saving on NI contributions. For example, if employer and employee contribute a combined £40,000 via salary sacrifice, there is no income tax, and the employer saves 15% in National Insurance, while the employee saves their own NI contributions. This mechanism, which is especially attractive for high earners, further widens the gap between those at the top and bottom of the earnings ladder in terms of government-supported savings.

–

The Power and Pitfalls of Compounding

–

One of the greatest advantages of starting pension savings early is the impact of compound returns. Money invested in a pension grows not just from the returns on the original investment, but also from reinvested gains over time. This means that the earlier someone starts saving, the larger their pot is likely to be in retirement—even without making larger contributions.

–

However, it is also true that for many people, earnings are lower earlier in their careers, and significant pension contributions become possible only as incomes rise. Thus, it is not merely the mechanics of tax relief, but the interaction between earnings, contributions, and compounding returns that shapes retirement outcomes.

–

Towards a Fairer System: Proposals for Reform

–

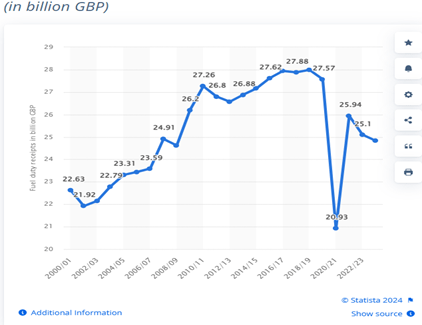

Given that pension tax relief is, in effect, a form of public expenditure—costing the Treasury billions each year—there must be reasonable limits. Otherwise, there is a risk that these generous incentives primarily serve those who need them least, while failing to promote adequate pension saving among those on lower or middle incomes.

–

Recognising the imbalances, I propose several reforms to the current system, with the twin aims of encouraging early and sustained pension saving while ensuring that the benefits of government support are more evenly distributed.

–

1. Flat-Rate Tax Relief

–

Rather than linking the rate of pension tax relief to an individual’s marginal income tax rate, I propose a flat rate of 25-30% for all taxpayers. This would mean everyone receives the same percentage uplift on their contributions, making the system simpler and fairer. Basic-rate taxpayers would receive a higher subsidy than they do today, while higher earners would see a reduction, but still benefit from a meaningful incentive to save.

–

- Example: At a 30% flat rate, a £1,000 contribution attracts £300 in tax relief, regardless of income.

–

2. Addressing Salary Sacrifice and Employer Contributions

–

The current system allows significant savings via salary sacrifice, especially for companies and high earners. To address this, I would introduce an employer National Insurance charge of 12.5% on all sums paid into a pension via salary sacrifice. Simultaneously, I propose reducing the general employer NI rate from 15% to 12.5%. This would help to neutralise the cost for employers overall while removing an unintended subsidy favouring the highest earners. This will help simplify the national insurance system and for those who employ lower earners, would encourage job creation.

–

3. Eliminating the £100k “Tax Trap”

–

Currently, individuals lose their tax-free personal allowance on income between £100,000 and £125,140, resulting in an effective marginal tax rate of 60%. I would remove this taper, restoring universal access to the personal allowance and ensuring that everyone is treated the same by the tax system, regardless of their income.

4. Lifetime Cap on Tax-Privileged Pension Benefits

–

I suggest introducing a “lifetime tax relief allowance” for pensions, capped at £300,000 in today’s terms. Over a working life, this would allow an individual to receive up to £300,000 in government-funded tax relief, not an insignificant sum. This is based on a good target of a £1 million pension pot (30% of which would be tax relief), which is more than sufficient for a comfortable retirement for most people. Removing the current lifetime allowance on the pension pot itself would ensure that those who wish to save more can do so, but without further subsidy from the taxpayer.

–

5. Reforming Inheritance Rules for Pensions

–

I propose reinstating the ability to pass up to £1 million of pension wealth to one’s children free of inheritance tax, provided it is used to fund a pension for them. Any pension assets above this amount or not taken as a pension would be taxed at 20% upon death if not taken as a pension. This recognises the contribution of tax relief to the pension’s growth while ensuring a reasonable transfer of wealth.

–

6. Fairness for Families and Partners

–

Upon drawdown, I would allow pensioners to split their income with a spouse or long-term partner, recognising the reality that many partners (often women) take time out from the workforce to raise children or care for relatives, resulting in smaller pensions. The current system does not allow for easy redistribution of pension income within households, despite both partners often contributing equally to family finances.

–

Balancing Generosity with Sustainability

–

It is important to emphasise that pension tax relief is fundamentally a taxpayer-funded benefit. While incentivising pension savings is essential for both individuals and society, the system must not become a vehicle for the wealthy to accumulate disproportionate advantage at public expense. By setting clear and reasonable limits, applying relief at the same rate for everyone, and simplifying the rules, the system can be made more transparent and more inclusive.

–

Conclusion: A Balanced Policy for the Future

–

A reformed system, as outlined above, would preserve the incentive for all individuals to save for their retirement while reducing the disparities that currently favour higher earners. It would also recognise the shared responsibilities of employers, employees, and society as a whole in providing for old age, while ensuring the system remains affordable and sustainable in the long run.

–

In summary, my proposals would:

- Introduce a flat, universal rate of pension tax relief (25–30%)

- Remove the £100k tax trap

- Cap lifetime tax relief at £300,000 per individual

- Adjust employer National Insurance to prevent salary sacrifice loopholes, while lowering the overall rate

- Allow fairer inheritance of pension wealth up to £1 million

- Permit spouses and long-term partners to share pension income upon drawdown

–

These changes would create a pension system that is simpler, fairer, and more equitable—one that rewards early and consistent saving, supports families, and reflects the principles of a modern welfare state.

Leave a comment